What is money, really?

Or, how to think about fiat currency, gold, Bitcoin and their future

Welcome to Fully Distributed, a newsletter about some of crypto’s most exciting projects, business models, and tokenomics!

Join our growing community by subscribing here:

Whenever bitcoin comes up in conversation (which happens increasingly often these days), I often hear skeptics push back with statements like

"Bitcoin has no intrinsic value"

"Why would I ever invest in something that doesn't produce cash flow? I'd rather own stocks"

"Bitcoin is too volatile to ever become a global currency or a store of wealth"

While only time will tell whether the Bitcoin experiment will endure over the coming decades, I began to ponder about the roots of such widespread skepticism around the world's largest cryptocurrency. Do people doubt the underlying blockchain technology or is there something else at play here?

Taking a step back, I realized that most people don't really think about what money is - or what underpins it - to most of us money is just something we all grew up using to pay for stuff. Especially for those living in the West, money has been a relatively basic part of their daily life - they haven’t experienced large scale currency devaluations or had to worry about high inflation (until recently…).

This post will explore the concept of "money" and provide a few mental models to think about our current monetary system and some of the alternatives for storing wealth. In particular, I will cover the following:

Money 101 (What is money?)

The First Hard Money (Why gold?)

Does money supply even matter?

Can US Dollar remain the reserve currency?

Money 101

In simplest terms, money is just a medium of exchange that provides us with an efficient way to transact with one another. As an alternative to the barter system (e.g. exchanging 12 apples for 8 bananas), money provides us with a common unit to pay for goods and services.

It is generally accepted that for something to be a reliable medium of exchange, it must possess salability - the ease with which it can be sold in the market with the least erosion in its price. Money's relative salability can be assessed in terms of:

Salability across scale - how easy is it to divide into smaller units (for smaller transactions) or grouped into larger units (for larger transactions)?

Salability across space - how easy is it to transport around / carry it along as the holder travels?

Salability across time - how well can it hold its value into the future?

While the importance of the first two properties (scale and space) are fairly obvious, salability across time is worth diving into a bit deeper.

Generally speaking, for a good to function as a robust store of value over time it should possess two properties:

It must be very hard for producers to significantly increase its existing supply in response to its price appreciation (the harder to increase the supply, the "harder" the money is said to be).

It must be resilient to erosion / damage / destruction.

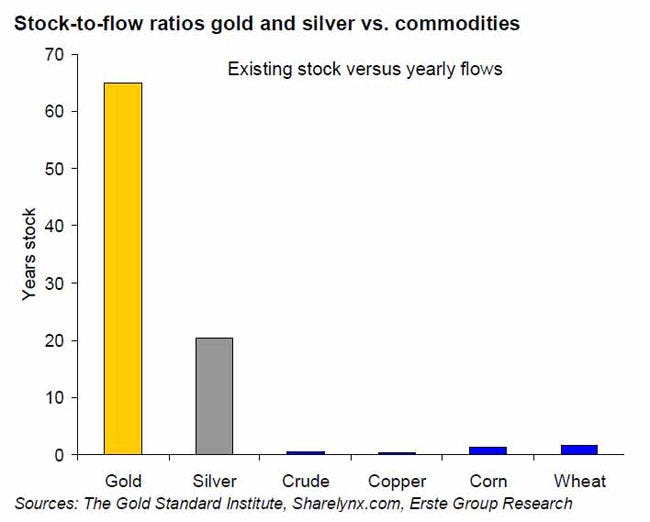

Therefore, when evaluating the relative "hardness" of money, it is helpful to look at its "stock-to-flow" ratio, which consists of the following two components:

Stock - existing circulating supply of a good less any quantity consumed or destroyed in the period

Flow - expected new production in the next time period

This ratio should be intuitive - the higher the existing supply of a particular good relative to the expected growth in its supply, the less impact this new supply will have on its price and vice versa.

Let's look at the following abstract example:

As can be seen, Good A has a much lower stock-to-flow ratio, which means that its supply can be dramatically increased year-over-year, which can result with oversupply (and therefore substantial reduction in its value). Meanwhile, Good B’s supply growth is small relative to existing inventory, which will have little to no impact on its price.

The First Hard Money

Although throughout human history money has existed in numerous forms - cattle, seashells, beads, copper, silver, and gold to name a few - the clear winner has been gold, which is still widely held by most central banks and federal reserves.

To illustrate why gold became the dominant store of value, let's compare copper and gold as stores of value. While both have been used as stores of value in the past, there are several critical distinctions between the two:

Copper:

Very abundant on our planet - there are roughly 5.8 trillion pounds of known copper resource on Earth of which only ~12% has been mined throughout history.

Has by far the highest recycling rate of any other metal (nearly as much copper is recovered from recycled material as is derived from newly mined ore).

Has many industrial applications - virtually all new supply is consumed, not stockpiled. This results in very low circulating supply of copper relative to annual production (e.g. low "stock-to-flow" ratio), which means that whenever copper prices rise due to excess demand, producers can easily flood the market with new supply (ultimately bringing the price back down), making it a poor store of value, with its price highly correlated to the economic cycles.

Gold:

Very scarce - it cannot be synthesized from other materials and can only be obtained from unrefined ore which is extremely rare on this planet.

Has very limited industrial applications and is nearly indestructible, which results in virtually all of new gold production being stockpiled, which steadily grows circulating supply.

Given that gold exploration has existed for millennia, existing gold stockpiles are massive relative to annual gold production in any given year, resulting in very trivial growth of existing supply (over the past 70 years gold stockpile growth has averaged ~1.5% per year, never exceeding 2%) . This means that even in times of steep price appreciation (due to higher demand for gold as store of value), producers cannot materially influence the price of gold even if they double their production.

To illustrate this point, I include stock-to-flow ratios for some of the most common commodities.

For these reasons, gold has been historically an excellent store of wealth across time. However, in its raw form it was very inconvenient to use - it’s heavy to carry around and hard to divide into smaller units. To enhance gold's salability across space and scale, gold was minted into coins by most civilizations, invigorating a global gold trade. However, given lack of standardization of coins across the world (some coins contained 4 grams of gold, while others contained 9), its salability across space was still suboptimal, limiting the scope of trade between countries.

The Rise and Fall of The Gold Standard

To address this issue, some nations began to switch to paper money backed by gold held in vaults. Each nation's currency was backed by different quantities of physical gold, making conversion as simple as switching between different measuring units (e.g. converting miles to kilometers or pounds to kilograms). For example, the British pound was defined as 7.3 grams of gold while the Deutschmark was backed by 0.36 grams, implying an exchange rate of 20.3 Deutschmarks per 1 British pound.

Britain was the first of many nations to adopt a modern gold standard in 1717, making gold more marketable and incentivizing other nations to join as well. By 1900 ~50 countries were officially on the gold standard. This was the closest the world has ever come to having one global currency, generating record capital accumulation, global trade and rise in global living standards.

This de facto global gold standard was interrupted by the outbreak of World War I in Europe. The tremendous increase in military and defense spending put significant pressure on nations' finances, which were constrained by the amount of gold they owned. As funds began to dry up, governments were left with very few options to choose from to get more money:

Increase taxes to increase government revenue - this was politically and logistically impractical to do at the time of war

Increase national debt - this would be a very costly source of funding given excess demand for loans and its limited supply, resulting in unsustainably high debt service costs moving forward

Inflate the money supply (print money) to pay off expenses - this would require the abandonment of the gold standard

Most nations ended up employing some combination of Options 2 & 3, which resulted in an explosion in their national debt/gdp ratios, as well as a rapid increase in their money supply. Printing money proved to be particularly addicting since it was the most politically palatable - it enabled politicians to increase spending without having to re-allocate funds from other government programs or increasing taxation. Indeed, moving away from the gold standard enabled governments to indulge in spending that they could not previously afford - they were no longer constrained by government revenues they collected through taxation.

Even to this day, long after World War I and II, governments continue to inflate its money supply to meet its ever so expanding spending programs (welfare, healthcare, military, infrastructure, protectionist subsidies for unprofitable domestic industries, etc). Between 1965 and 2015, the global annual money supply growth has averaged ~35%, while the top 10 biggest currencies have grown its money supply at a more modest 7-10% per year.

While 7-10% may not sound like a lot (especially when compared to the global average), such growth rate would still result in the doubling of the money supply every 7-10 years, effectively diluting the incumbent currency holders by 50%! While global reserve currencies (i.e. USD today) may get away with it for longer, consistent increases in money supply will always result in currency devaluation.

Does Money Supply Even Matter?

A helpful mental model to understand the importance of money supply growth is to think of hypothetical company that issues 10% of its market cap in new equity every year. Would you be ok with that as a shareholder? Well, it depends. Let's look at three hypothetical examples:

As can be seen in the tables above, in all three cases, an annual 10% issuance of market cap results in ~50% dilution of shareholder's ownership interest in the company. However, what really impacts the net worth of the shareholder is the relationship between annual growth of the company and the new equity issuance:

Company A's growth offsets the dilution, resulting in a ~37% increase in shareholder wealth by year 7

Company B's growth is equal to the dilution, resulting in no change in shareholder wealth

Company C's growth is less than the dilution, resulting in a ~28% reduction in shareholder wealth by year 7

Similarly, when evaluating the impact of any given country's money supply growth on purchasing power, one must consider the real growth of the economy that may or may not offset the inflation of the money supply. If the newly created money is used productively (e.g. infrastructure, healthcare, education, etc.), it will be highly accretive to that country’s economy and generate real GDP growth. However, if the new money is not used productively (e.g. spent on non-productive financial assets), it will result in the gradual devaluation of that currency (and result in the increase in the value of those assets).

With that in mind, no developed country has achieved average economic growth rates of 7-10% over this 50 year period (for instance, US has averaged only 3.2% since 1948), which results in significant dilution of the purchasing power in each of those countries. Of note, this analysis excludes the impact of COVID-19 pandemic, which resulted in a ~46% increase in money supply in 2020-21 alone (from ~$15 trillion to $22 trillion), sparking wide long-term inflation concerns.

Inflating the money supply (and thereby reducing the currency's purchasing power) to fund government spending that it cannot afford can be viewed as government's expropriation of wealth from its people. To make matters worse, easy monetary policy disproportionately impacts lower income people, who are more likely to not own any inflation-resistant capital (e.g. real estate, stocks). Instead, they largely rely on their nominal wages to fund their day-to-day life, only to see their purchasing power evaporate over the years.

Can Government Effectively Control Money?

To explore this question, let's consider a hypothetical coffee plantation in Brazil responsible for 30% of the world's coffee bean production. Let us assume that it unexpectedly gets struck by a drought, which destroys the entire crop for the year, resulting in a significant global shortage of coffee beans.

Scenario 1

Global shortage results in a sharp increase in the global price of coffee

Hundreds of thousands of individual coffee purchasers (coffee shops, restaurants, grocery stores) adjust their purchasing orders down based on their detailed analysis of expected customer demand in response to the price increase, resulting in reduced global demand for coffee

Thousands of coffee producers ramp up coffee production based on their detailed analysis of unmet customer demand, resulting in an increase in global supply of coffee

A combination of reduced demand and increased supply results in the stabilization of the global coffee prices, resulting in a new efficient market price at close to pre-drought levels

Scenario 2

To prevent significant market volatility, each country's government decides to set the new coffee price based on their top down analysis of the market supply and demand dynamics

New coffee price no longer reflects the collective buying and selling decisions of coffee market participants, distorting economic reality of the market

Individual coffee purchasers end up buying too much or too little coffee, while individual coffee producers end up producing too much or too little coffee

Since the market is unable to clear at a new efficient price (given government's centrally planned price), coffee market endures significant economic deadweight loss for both coffee producers and consumers

In this hyperbolic example, Scenario 2 would result in a complete disaster - no government is able to accurately forecast the correct efficient price (or production level) of a good on behalf of thousands and thousands of market participants. In a functioning economy, the price is the output based on collective actions of market participants that act in their own self interest. To make matters worse, markets are inherently highly dynamic and are constantly impacted by the constantly changing buyer and seller preferences, making it that much harder for any entity (let alone a government) to accurately calculate it.

So just as it is impossible for a government to centrally plan the coffee market, it is equally impossible to centrally plan the market for capital - whether it be its price (interest rate) or liquidity (money supply). As such, a centrally planned loose monetary policy results in suboptimal capital allocations throughout the economy. For example, an artificially low interest rate incentivizes reduced saving and increased spending, which results in reduced capital accumulation. At the same time, it encourages increased borrowing and enables unprofitable projects getting funded.

Government's control of its money supply has permanently increased the role the government plays in our day to day lives. During the international gold standard, foreign exchange rates were relatively fixed and the purchasing power of the gold-backed money was stable. People’s economic well-being was largely a product of their own economic input. In the era of the fiat money, our wealth now depends on the centrally planned fiscal and monetary policy (which directly affects our purchasing power) and relative currency fluctuations (which are affected by trade policies set by the government).

Can US Dollar Remain the Reserve Currency?

So what will happen to the US Dollar in the future? Is fiat money here to stay?

There are several factors that keep government money reigns supreme in our society:

Banks can only open accounts in government-sanctioned money

Legal tender laws make it illegal in many countries to use other forms of money for payment

Taxes have to be paid in fiat

Taxation is by far the biggest competitive advantage that government money has over other alternatives - it’s what gives it its stability. Government can flex taxes (to raise its revenues) to buy and stabilize its own currency. Additionally, governments (and banks) needs to be able to track money flows between market participants to prevent tax evasion, money laundering, terrorist financing, etc. In short, I do not expect fiat money to go away any time soon.

With that said, I do not expect fiat currencies to function as robust stores of wealth over the long-term - even the US Dollar. Why? Simple math.

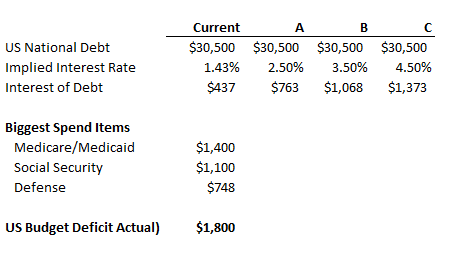

At the time of writing, the United States has ~$30 trillion of debt, a lot of which has been raised in a historically low-interest rate environment (1.4% blended cost of debt). As we are heading into a high-inflation environment (latest CPI has clocked in at 8.6%), the Fed will be forced to start raising rates to stifle inflation. For every 100bps increase in rates, government’s debt service will increase by ~$300 billion. At the same time, the government is already running a $1.8 trillion budget deficit!

Rising debt service costs will only put additional pressure on the budget deficit. I am not even mentioning all of the underfunded state pensions and social security - all of which will likely have to get bailed out by the government in the future.

So what does this all mean?

The US government has very few options left to meet its future obligations - it WILL have to keep printing money to avoid bankruptcy (raising taxes or cutting spending will be hard both politically and economically). This means that the US Dollar will continue to get devalued over time until a new reserve currency with more sound monetary policy will come to dominate global trade.

To be clear - I do not expect fiat currencies to disappear - nor do I predict the US Dollar to hyperinflate in the next few years - but at different times throughout history we’ve had many reserve currencies (e.g. Dutch Gilder, British Pound, etc.) and they all had the same fate - they were all devalued by overindebted governments to fund its liabilities, giving way to a new reserve currency to emerge.

This is exactly why gold has been such a strong store of wealth over millennia - it has been the only money with a sound ‘monetary policy’ - that is, until Bitcoin was invented, which shares most of the same properties (indestructible, immutable inflationary profile, scarce finite resource).

For Bitcoin to displace gold the world will have to buy into its similarities to and advantages over gold at scale - only time will tell if this experiment succeeds. But one thing is certain - both gold and its digital equivalent will never hyperinflate, nor will its supply be ever controlled by any sovereign state.

We are all in for quite a ride over the coming decades. Stay safe.

Disclaimer: None of this is financial advice. Do your own research. The author may hold long positions in gold and Bitcoin at the time of writing.

Great article!